I tell students at the beginning of the school year that science is a descriptive discipline. The goal of a scientist is to see phenomena and attempt to accurately convey what we observe. There is a tremendous amount of beauty in the world that we rarely see because we think it’s commonplace and so seldom notice.

In order to accurately convey what we observe, we need to learn how to look at things. This is a bit trickier than it sounds. The challenge with looking is that when we look at something, we think that we see all of the important information right off the bat.

But the interesting details of life only appear to us when we spend a long time consciously looking at something. This is why you can look at a particular object a hundred times and still capture new details—your brain filters so much information unless you devote significant time to staring at something and studying it.

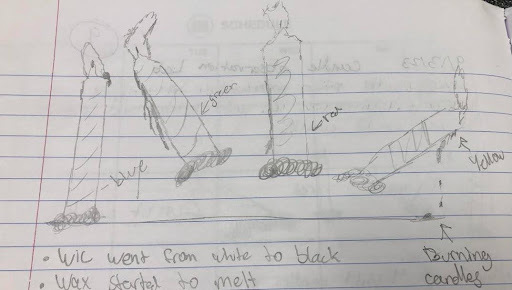

One of my main goals as a science teacher is to open students up to seeing all of those beautiful and interesting details. I do that by having students draw things and clearly write what they observe. Drawing something requires students to look at their subject far longer than they are accustomed. Writing what they see forces them to consciously acknowledge it. I explain to students that just as every single human is unique, so is every coin, plant, and salt crystal.

The phrase “a picture is worth a thousand words” is accurate precisely because the human brain is amazing in terms of capturing and interpreting visual information. The student’s job is to capture and share those details that aren’t easily seen as best they can.

Student Pushback

Many students at first dislike this activity. I’ve been told:

- “This isn’t fair—you’re discriminating against the untalented!”

- “I can’t do this—I have astigmatism.”

- “This is exacerbating my anxiety!”

- “I thought with my dysgraphia I would never be able to do something this clear!”

- “Why did I hate art?”

- “I never thought I could spend 20 minutes focusing on anything, let alone on candles!”

Courtesy of Selim Jamil

Greater Clarity and Retention

Drawing works to improve learning for almost any subject. For my own learning I find that when I can draw whatever it is that I am attempting to understand, I retain significantly more information. Because it takes time for me to draw something, my brain is spending significantly more time thinking about whatever I am focused on. As a result, I increase my intuitive leaps; my brain makes more connections the longer I spend looking at something.

There are some people who have figured out how to memorize and retain large amounts of abstract data. That is wonderful. But I believe that many people, who struggle with understanding and retaining abstract information, should try and find opportunities to draw the information they need to know in order to retain it. Many people have told themselves that they are not able to understand a concept when in reality they have not presented themselves with the information in a way that their brains can value and comprehend.

For anyone interested in trying to improve their drawing, or their students’ ability to draw, I recommend the following tips to get started.

4 Ways to Improve Drawing Skills

1. Look at the object, not at your drawing. Your inner critic will stop you if you give it the opportunity to judge your work. If you look at the object, your brain will do an amazing job of guiding your hand with minimal effort.

2. Seek out geometric shapes of the big picture. Every image can be broken down into fundamental geometric shapes. When we see that big picture, it becomes a lot easier to draw something. For example, to draw a bird, start with the triangles of its beak and wings and the oval of its head, eyes, and body.

3. Draw the outline and don’t focus on the details. People often try to draw the little details perfectly instead of trying to get the gist of the image. It’s like trying to write a perfect sentence when you don’t know what you are writing about yet—it won’t work because the details only make sense in the context of the work as a whole.

4. If “drawing” is too intimidating, feel free to “doodle.” Becoming a good artist is not the goal; using our natural visual gifts to clearly see and understand reality is the goal.

If you discover new insights after drawing something, then by definition you’re an artist! Drawing was far and away the best discovery I made in my late 30s—it has helped me tremendously and it can enrich you no matter when you start.

![Why Is Forgiveness Important? [For Yourself And For Them]](https://familyfocusblog.com/wp-content/smush-webp/2020/02/why-is-forgiveness-so-hard-634x423.jpg.webp)